The victory of Deep Blue against Kasparov in 1997 is a typical milestone mentioned by artificial intelligence researchers. Playing chess as a symbol of intelligence was an early idea even mentioned by Alan Turing back in 1950, in the famous imitation game paper.

Chess game is even today used as a landmark to compare and explain difficulties in creating AIs or robotics projects. It is also worthy highlighting than in 1997 the RoboCup project started:

When established in 1997, the original mission was to field a team of robots capable of winning against the human soccer World Cup champions by 2050.

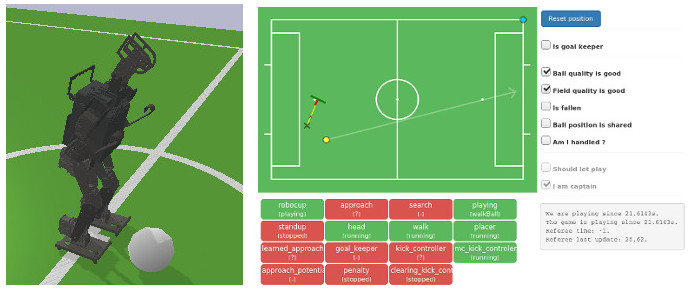

I am member of one of the teams competing in humanoid league (kid size) of RoboCup since 2013. You can have an insight on the current state with this short video:

So, how fielding a team of humanoid robots playing soccer against humans is still hard while we can defeat the chess grandmaster?

High dimensions and continuous space

Recent breakthrough in artificial intelligence is deep reinforcement learning, which most impressive applications can be credited to DeepMind and OpenAI, including:

- AlphaGo, playing the Go (board game)

- Playing Atari Game (video)

- AlphaStar, playing the Blizzard’s RTS video game StarCraft II

The difference in difficulty was depicted by Deepmind on the following slide during the Blizzcon 2019:

Actions and states spaces are continuous

In chess game, action space is discrete. You can enumerate all the possible moves in a given state. Having discrete actions is convenient from computational point of view, because it allows sweeping, you can at some point consider all of them one by one. This is typically what is done in Deep Blue (min/max exploration).

Even the Atari Games AI builds a model that given a state (e.g: the screen of the game) and an action (e.g: pressing the button “up”) computes a score of the future rewards (e.g: the score). Once you have this model, you can take the action that maximize this score for the current state, by evaluating the model for each possible action.

Other AI architectures (like DDPG) can deal with continuous action space and also builds a model of a function deciding what action to take depending on the current state (so-called “actor”).

In robotics, actions and states are mostly continuous, because actually physical, like how much volt should we inject in a given motor? Moreover, in the low level layers, those decisions are made at high frequency (typically hundred of times per seconds). The state of the robot typically includes numerous degrees of freedom, possible backlash/flexibility/sliding (that can be seen as passive degrees of freedom).

That is why we need to do dimensions reduction:

- Can we make decisions less often?

- Can we use only a subset of the robot possibilities?

- Can we split up our problem in different parts, that separately have lower dimensions?

Uncertain information

Information is partial

of partial information

The information available for a robot at a given point is only a partial approximate view of its environment. This is because the environment itself is the physical world which is very complex and not all of it can be captured.

Moreover, taking information is itself part of the decision process, think about where you decide to look at when discovering a new building and try to navigate.

Noise

Sensors can be said to be noisy. However, noise is just a natural way to represent the fact that information is partial, using a probability distribution for the state of the robot.

Suppose your robot is kicking a ball on a grass field, the ball is rolling and will reach a position. If you repeat this experiment several time, the ball will reach different position. This is because the initial conditions changes, and the kicking motion itself might not be exactly the same. Of course you can improve your motion and perception, but it is unlikely your robot will capture exactly all the blades of grass, its own initial pose or the ball inertia.

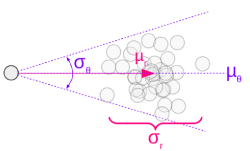

Thus, you use a probabilistic model like this one:

It means that you will have to take in account that for each kick, the ball will not reach exactly a given position, but will instead follow a given distribution. This noise is actually some way to spread the uncertainty about information in the decisions layers of the robot.

Deal with physics, mechanics & embedded

Unlike StarCraft II or AlphaGo, robotics involves real-life hardware (mechanics, electronics) that should be designed and scaled for the task.

Joint design

There is still plenty research about how to design good robotics joints, and potential breakthrough in the future might be total game changers in robotics design.

Low-cost robots involve serial gears that can easily break and introduce backlash. Industrial robots relies on harmonic drive reduction, that is very efficient but also really rigid. This rigidity is not suitable when it comes to passive or semi-passive robots, which is natural idea when thinking of bio-inspired designs. Think about your legs when walking, most of the motion is actually totally mechanical (your floating leg is only actuated a little).

For example, I built last year a robotics dog, using good quality (still hobbyist) MX-64 servomotors. Using cubic splines interpolations with inverse kinematics model of legs, it was performing quite good on flat floor, but it is a disaster on uneven ground without further adaptation.

It is clear that a baby human learning to walk has a quite different strategy, almost throwing its legs forward randomly and keep balance once it reached ground.

Rigid robots are less likely to adapt their environment and to cooperate with humans. With this goal in mind (we talk about soft robotics), there is different leads:

- Using series elastic actuators, where a spring is on the way between motor and load

- Creating different reduction technologies (like cycloidal)

- Using motors with more torque with smaller reduction ratios

CYBO project in following video is a good example of such investigation:

Physics is a model of the world

We should not forget that physics itself is an experimental science, and even the best equations we have are just models of what we experience. Moreover, those equations are computationally expansives and in real-life application only simpler models can be used.

This experimental aspect means that doing actual experiment is at the core of robotics, and benchmarks, or at least videos of a given robot performing tasks is also scientifically interesting.

RoboCup provides one of those benchmarks, however it does it the hard way, because you are not benchmarking a specific task but a whole behavior (more like functional testing than unit testing).

Integrating everything together

Robotics is multi-fields

Creating a robot involve several skills, like mechanical design & manufacturing, electronics, embedded, kinematics… If you want to build something real, you need to be at least a little good in every one of those layers.

This can be noticed in any league of the RoboCup, getting real robots working and ready on time for a given challenge is really demanding. It is common in a laboratory to have people working in standalone on their own research field, but impossible in a robotics team making real robots, since this requires both infrastructure and a group of people collaborating with common goals.

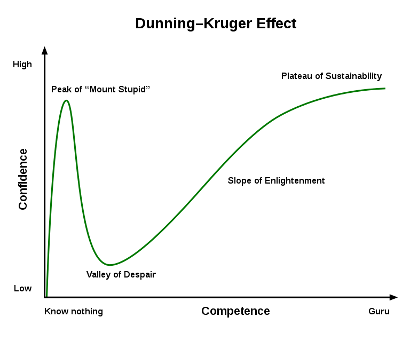

Not to mention that with the Dunning-Kruger effect, if you are a little good in a lot of topics, you are also in a lot of valley of despairs (i.e: by understanding better each sub-fields you also understand how much they can be improved).

Moreover, integrating different parts together in a robotics project is a real work that should not be taken lightly.

The what-to-improve dilemma

Especially in research, projects involve field-specialists. However, don’t forget the law of instrument:

If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail

It is then likely that computer scientists will try to fix the problems out with machine learning, while control theory expert will ask for a higher sampling rate and mechanical engineer will want to use lighter screws.

That is why to get something working you need to have a critical view on each point, but also being able to take action in both high-level software and low-level embedded systems whenever necessary.

Don’t forget the Pareto principle, 20% of our actions gets the 80% results, and trying to fix an issue using the wrong approach just because we are blinded by our own field is one of the reasons why it is like that.

Testing is hard

When you commit code into some repository, you can expect it to be tested by your continuous integration server or at least some process that your colleagues will be able to run later. This is harder to setup in robotics, since your final functional tests themselves include a lot of hardware that communicate together.

However, separate components are still unit-testable. You quickly realize that a lot of your development effort is about handling the possible fake environments that allow you to test some piece of code without experimenting live on the robots themselves.

Moreover, being able to log and replay one component is also an important feature to have. This is one of the good value of the ROS project.

Conclusion

In my team, we try to master all the aspects of designing robots almost from scratch that eventually performs complex tasks, and this comes with a lot of difficulties. But getting the final functionning result is a quite satisfying feeling that makes those efforts worth it!

Gregwar

Gregwar

@greg_war

@greg_war